🧵 How to Be Gaslit by a Digital Pet

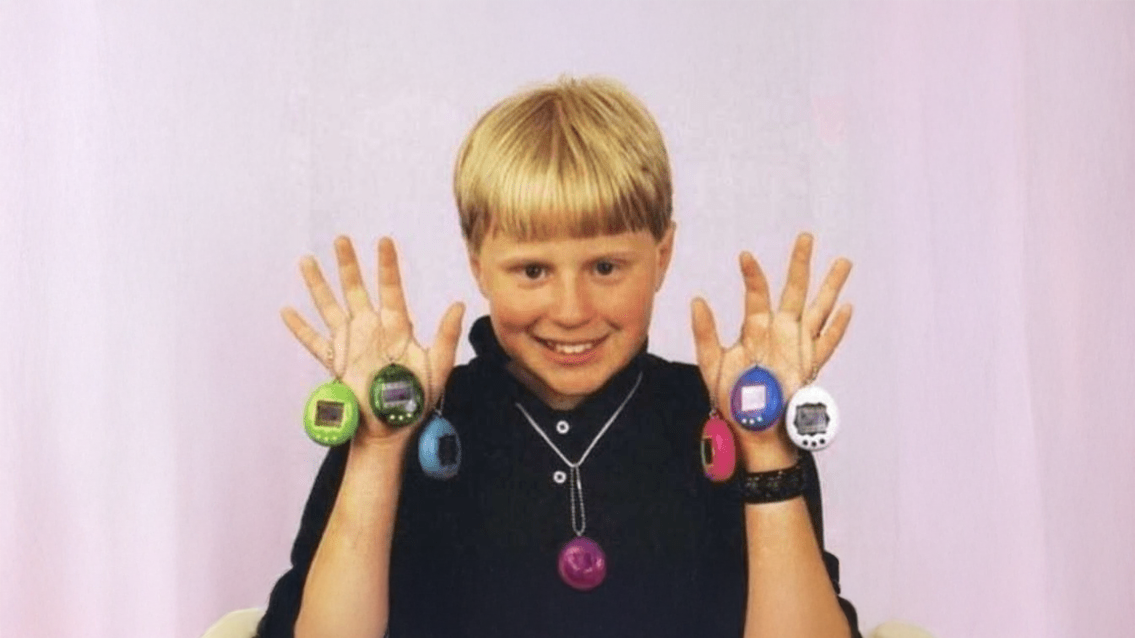

The UX of Tamagotchi

It starts innocently enough: you name your Tamagotchi something cute (like “Bean” or “Lord Poopeth”), feed it a pixelated meal, and think, Wow, I’m crushing this pet ownership thing. Fast forward six hours and it’s screaming at you in the middle of math class, hungry, angry, covered in poop, and on the brink of death. You were never the owner. You were …