A Love Letter to Plastic Junk: Nintendo’s weirdest Inventions

Why the loud, clunky gadgets of the 80s reveal what we've lost in the age of frictionless tech.

Look at a PlayStation 5 or an Xbox Series X today and you see a monolith. They are sleek, silent, matte-black or white towers designed to disappear into your media cabinet. They are 'frictionless.' They are optimized. And, frankly? They are a little boring.

Walking into a living room in 1989 was like seeing a crime scene of grey plastic. You saw a floor mat that looked like a Twister board, robots that didn’t work to gloves that looked like it was stolen from a cyborg.

For the last forty years, the tech industry has been obsessed with streamlining our lives. But Nintendo has always argued the opposite. They built an empire on the idea that play shouldn’t be smooth. It should be clunky. It should be weird.

Looking back at their island of misfit toys, I’m starting to think they knew something about joy that we’ve optimized out of existence.

The Philosophy of the “Toy”

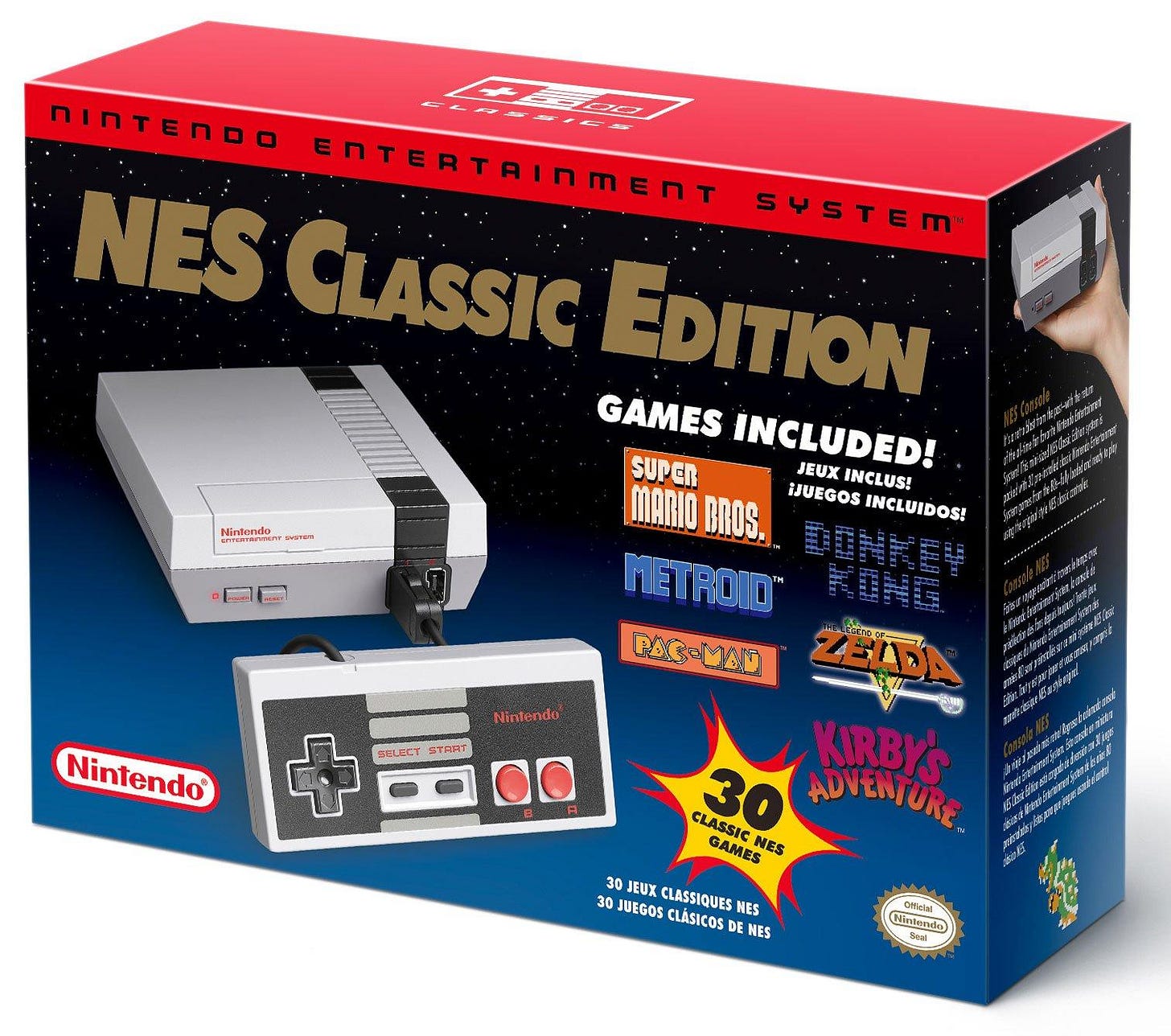

To understand why Nintendo made so much weird stuff, you have to understand the trauma of 1983. The American video game market had just crashed. Retailers treated “video games” like radioactive waste.

So, when Nintendo brought the Famicom to America as the NES, they didn’t call it a console. They called it an “Entertainment System.” And to prove it wasn’t just a computer, they packed it with a “Robotic Operating Buddy” (R.O.B.).

R.O.B. was a Trojan Horse. He was a slow, loud, battery-draining gyroscope spinner that only worked with two games. But he served a vital purpose: he made the NES look like a toy. He gave the system a physical presence in the room. This philosophy that gaming should spill out of the TV and into your lap became Nintendo’s defining DNA.

While Sony and Microsoft chased higher frame rates, Nintendo chased “Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology” (a philosophy coined by the legendary Gunpei Yokoi). They took cheap, existing tech and combined it in ways that forced us to play differently.

Sometimes it worked. Often, it was a spectacular, plastic failure. But looking back, the failures were almost more important. They proved that Nintendo was willing to be weird in public - a trait the rest of the industry has largely optimized away.

The Hall of Fame of “Why Does This Exist?”

Let’s take a walk through the museum of plastic ambition.

It’s important to remember the ecosystem these gadgets lived in. In the NES era, nothing was wireless. You had the power brick. You had the RF switch (that thick grey cable connecting the console to the TV). You had two controller cords—which were always too short. If you were playing Duck Hunt, you had the Zapper gun cord. If you had R.O.B., he had his own cables.

The result was a literal knot of rubber and copper on the living room rug that looked like a plate of black pasta. And in the middle of that mess sat these beautiful disasters:

1. The NES Zapper: The Satisfying “Clunk”

Modern shooters rely on haptic feedback and uncannily realistic triggers. The NES Zapper relied on a spring that sounded like a staple gun. CLUNK. CLUNK. CLUNK.

The Zapper was simple light-gun tech, but it felt crucial. It turned the television - a passive box - into an interactive shooting gallery. It wasn’t about precision (you could cheat by aiming at a lightbulb); it was about the fantasy. Holding that orange plastic heater made you feel like a cowboy in your pajamas.

2. The Power Glove: TheBad, The Bad and The Ugly

No peripheral in history promised more and delivered less than the Power Glove. Immortalized by Lucas Barton in the movie The Wizard, the Power Glove sold us a cyberpunk dream where we could control games with the flick of a wrist.

In reality, it was a motion-control nightmare that required you to tape sensors to your TV and punch the air hoping Mario would jump. It didn’t work. It was exhausting. But look at it. It has a number pad on the forearm! It has purely decorative “computer” graphics! It was unnecessary in function, but essential in aesthetics. It trained an entire generation to want the future to be wearable.

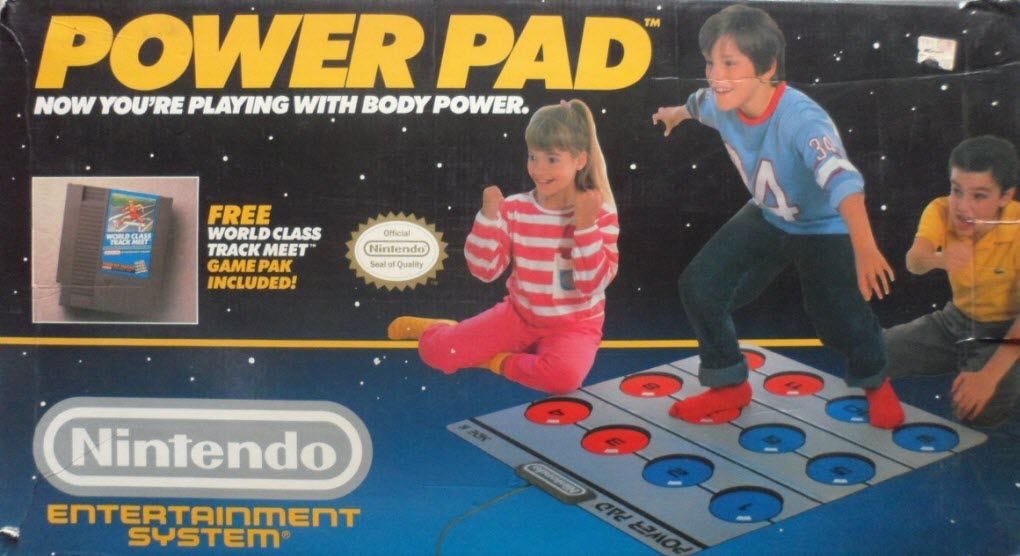

3. The Power Pad: The Original Gym Membership

Long before Dance Dance Revolution or Wii Fit, Nintendo asked us to take off our shoes and stomp on a flimsy sheet of plastic sensors. The Power Pad was huge, impossible to fold back into the box, and smelled intensely of vinyl.

It was designed for World Class Track Meet, a game where you had to run in place like a maniac to make your character move. It was the first time gaming demanded athleticism (or at least, rapid flailing). It proved that video games didn’t have to be a sedentary act.

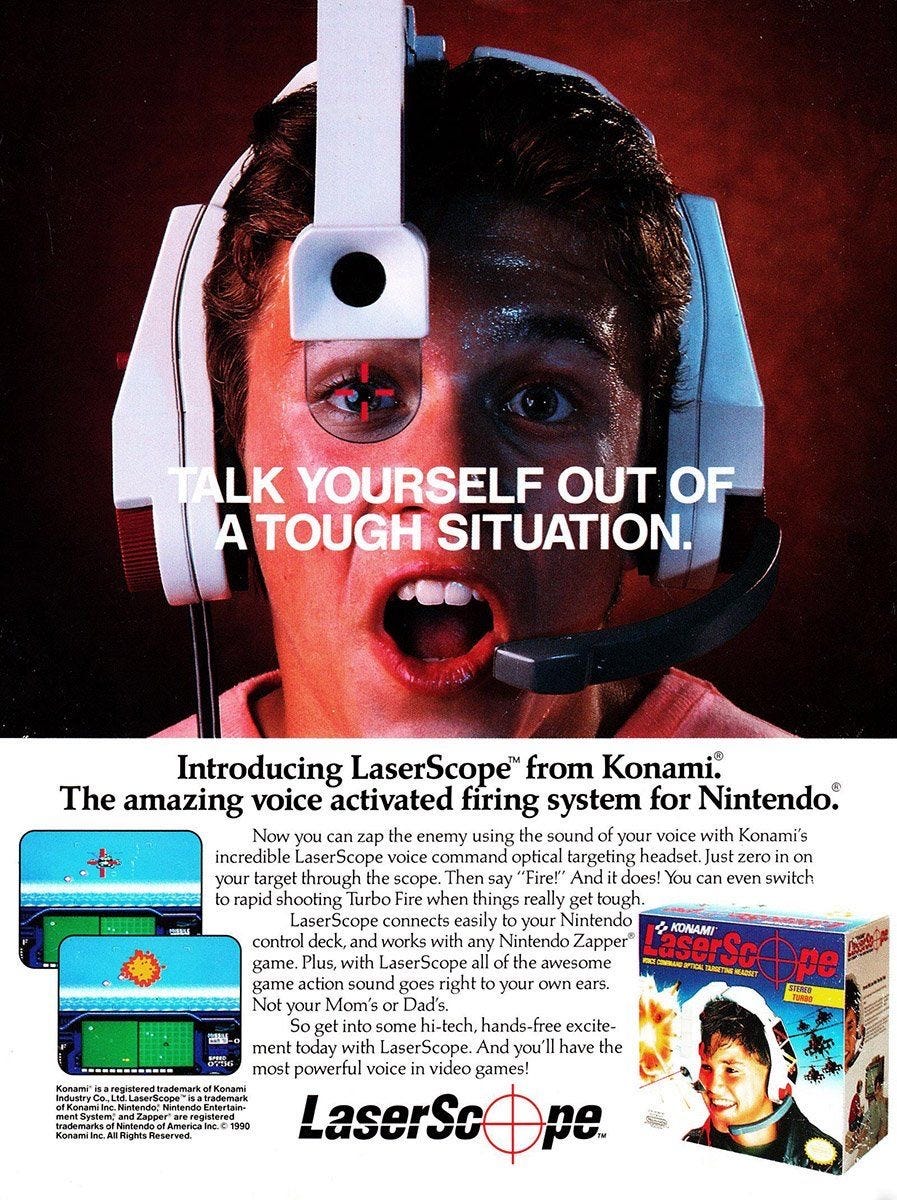

4. The LaserScope: “FIRE!”

This might be the most “1990s” object ever manufactured. The LaserScope was a voice-activated headset that supposedly let you shoot enemies by shouting “Fire!” at your screen.

It was essentially a Zapper strapped to your face with a microphone that picked up any background noise. Did your mom open the door? You fired. Did a dog bark? You fired. Did you breathe too heavily? You fired. It was a solution looking for a problem that didn’t exist. You looked ridiculous, you sounded crazy yelling at your TV and it was glorious.

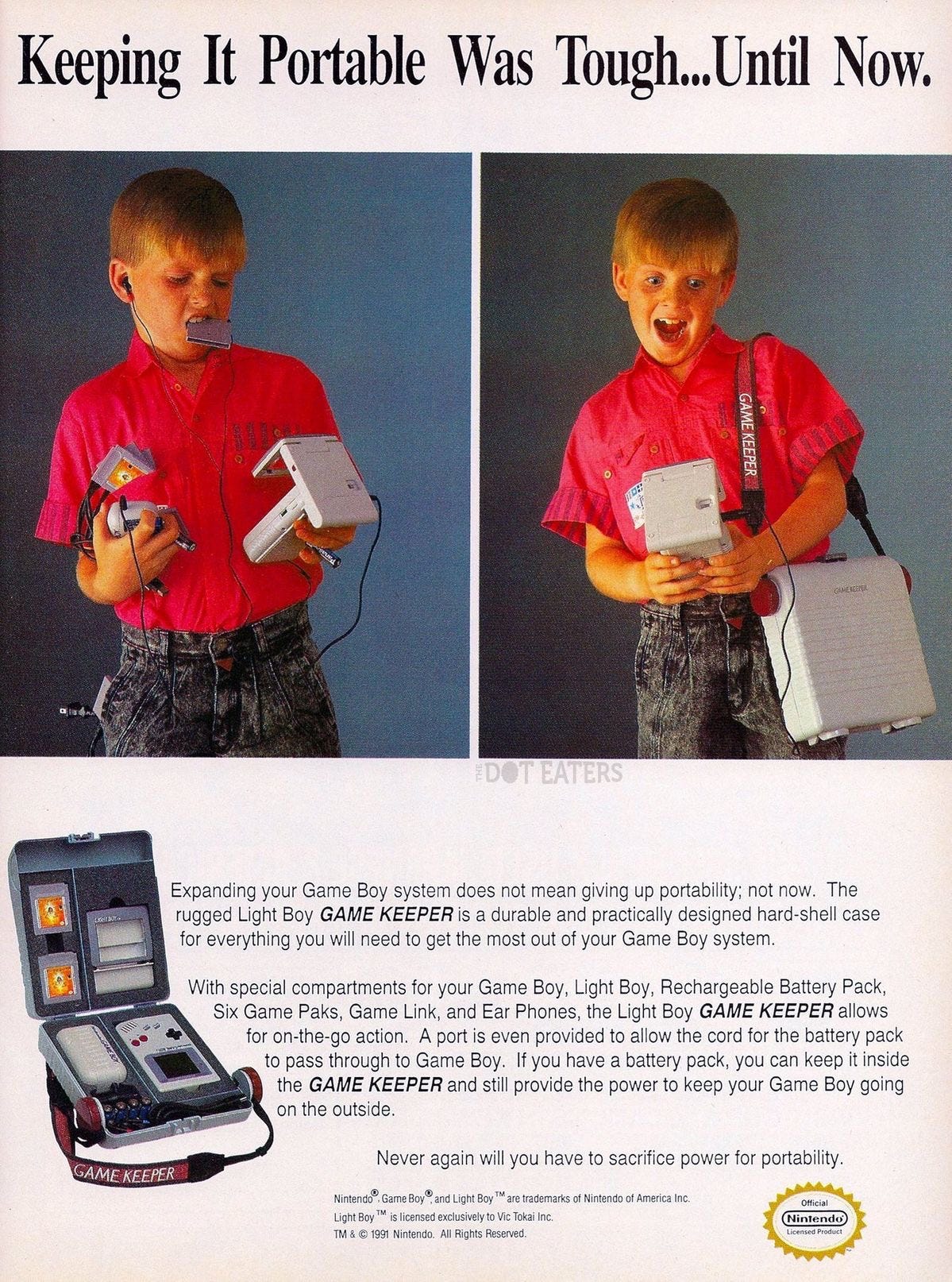

5. The “Franken-Game Boy” Phenomenon

The Game Boy was designed to be portable. But 90s kids were determined to ruin that. We bought magnifiers to make the screen bigger. We bought “worm lights” to play in the dark. We bought battery packs that clipped on the back like tumors.

The “Game Keeper” is the final boss of this trend. It’s a hard-shell briefcase that integrates the Game Boy, the light, the batteries and the games into a setup that weighs as much as a laptop. It defeats the entire purpose of the handheld, and yet, there is something charming about the urge to accessorize our tech, to armor it up until it looked like military hardware.

6. The Robotic Operating Buddy (R.O.B.): The Plastic Trojan Horse

R.O.B. was a desperate peace treaty disguised as a toy. In 1985, U.S. retailers treated “video games” like poison, so Nintendo bundled the NES with a robot to trick stores into stocking it as a high-tech plaything.

Playing with him was a test of patience. He moved with the agonizing slowness of a 19th-century clock, spinning gyros to press buttons on your controller while you waited. He only supported two games before being retired, making him a technical failure but a strategic masterpiece.

R.O.B. is the ultimate Hall of Famer because he proved that physical presence matters more than software. He didn’t need to be a good player; he just had to be there, whirring on your carpet, making the digital world feel real.

6. The Game Boy Pocket Printer

In 1998, Nintendo released a digital camera and a thermal printer for the Game Boy. The photos were grainy, 2-bit, black-and-white messes. You had to peel them off a roll of receipt paper.

And it was magical.

Its quality was also objectively terrible. But the act of printing made it feel permanent. We stuck those little stickers on binders and fridges.

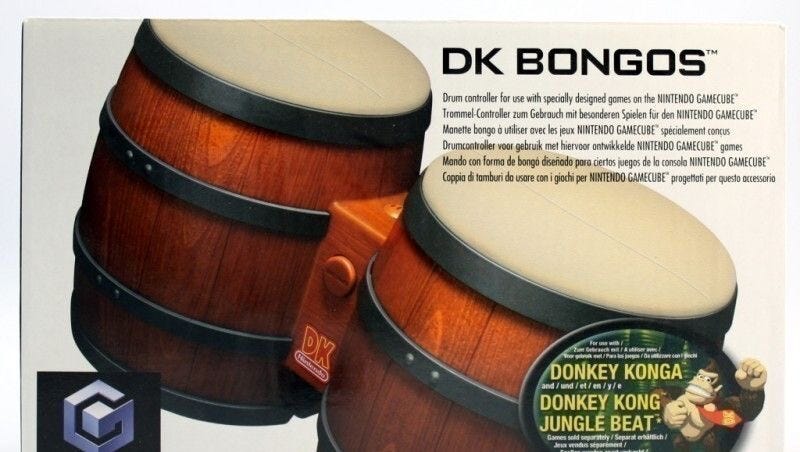

7. DK Bongos: The Specificity of Joy

The GameCube era gave us the DK Bongos, a controller that only worked for a rhythm game where you slapped plastic drums. It took up shelf space. It was loud. It was silly. But you cannot play Donkey Konga with a regular controller and have the same experience.

The absurdity was the point.

The Cardboard Renaissance

You might think this “clunky plastic” era died when the 90s ended. You’d be wrong. While the rest of the industry chases 8K resolution and ray-tracing, Nintendo is still out here selling us garbage. And we are still buying it.

In 2018, they launched Nintendo Labo. They asked us to pay $70 for sheets of literal cardboard. We had to punch out the shapes, fold them into fishing rods and piano keys and slot the Switch screen inside.

On paper (pun intended), it was ridiculous. But culturally? It was a flex. In an era of VR headsets and haptic suits, Nintendo proved they could still create “magic” with the cheapest material on earth. It was the Power Glove spirit all over again: the belief that the “video game” isn’t just what happens on the screen. It’s the ritual of building the controller.

It’s the friction of the cardboard rubbing against itself.

The “Vinyl” Theory of Gaming

There is a reason sales of vinyl records have surpassed CDs and digital downloads in recent years. Streaming Spotify is “frictionless”: it’s optimized, instant, and perfect. But it feels like nothing.

Putting on a record requires effort. You have to slide it out of the sleeve. You have to drop the needle. You have to flip it over. That friction forces you to pay attention.

Nintendo’s “unnecessary” inventions were the vinyl records of the gaming world. When you played with a Zapper or a Power Pad, you were engaging in a ritual. You had to set up the sensors. You had to untangle the cords. You had to hold a physical prop. That friction made the gaming session feel like an event. You weren’t just tapping a glass screen while waiting for the bus; you were physically interacting with a machine.

We’ve optimized the friction out of modern technology. We made it convenient, but we made it less memorable. I don’t remember downloading an update for my PS5. But I remember exactly what the plastic clack-clack-clack of the NES Zapper trigger felt like.

What We Lost When We Lost The Junk

We live in a better technological world now. The Switch is a marvel of engineering: a hybrid console that just works. The iPhone is a miracle of glass.

But in our rush to make everything seamless, we’ve lost the texture of play.

When you played with a Power Glove or a Zapper, you were engaging in a ritual. You had to set up the sensors. You had to untangle he cords. You had to hold a prop. That friction made the gaming session feel like a event. You weren’t just tapping glass; you were physically interacting with the machine.

These unnecessary inventions were Nintendo’s way of saying that imagination needs props. They understood that sometimes, to feel like a space marine, you need to hold a plastic gun. To feel like an athlete, you need to stomp on a mat.

We don’t need the Power Glove to come back (please, god, no). But we should celebrate that Nintendo is still weird enough to sell us folded cardboard and stop optimizing the fun out of everything.

Sometimes, the “unnecessary” parts are the only parts we actually remember.

Catch you next time,

Sarah